Bob Hawke was elected Federal Labor Leader and Opposition Leader, dramatically just as sitting Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser called a double-dissolution election campaign. Hawke campaigned with energy and confidence, expanding Bill Hayden’s strategy for Recovery and Reconstruction with a third overriding goal, Reconciliation. Campaign advertising was likewise redesigned around the new leader’s aspirations for Bringing Australia Together. On 5 March 1983, Labor won power.

With a primary vote of 49.5%, Labor won 75 seats in the 125-seat House of Representatives, including a majority of seats in every state and territory except Tasmania. The win inaugurated an unprecedented era of electoral success: the party’s longest period of office at the federal level. Labor was also in government in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia.

Hawke’s campaign theme of reconciliation expressed his ‘consensus’ approach to national political leadership. His signature promise was to convene a National Economic Summit. Within a week of his election, the new Prime Minister issued around one hundred invitations – to unionists, CEOs, industry lobbyists, government ministers, state premiers and community representatives - to gather in the House of Representatives chamber on 11 April 1983. The week-long summit, addressing the vulnerability of the Australian economy and the weakness of the budget, helped educate the public about the nation’s economic challenges. The communique provided a strong affirmation of national consensus in support of the new government’s economic recovery strategy.

Central to this strategy was the Accord. Agreed between the ALP and the ACTU on behalf of the trade union movement, the Accord was designed to break the inflationary cycle by slowing wages growth. But - in a critical distinction from prevailing conservative or neo-liberal prescriptions - the Accord required that workers be compensated for this wage restraint by improved ‘social wage’ income via increased government spending in health, education, housing and other social programs. A brilliant combination of the political and industrial wings of the labour movement, the Accord placed the union movement at the heart of economic policy making.

Labor’s introduction of Medicare on 1 February 1984 exemplified the Accord in action. A system of universal health insurance funded by a levy on taxable income, Medicare boosted the ‘social wage’ and fulfilled Labor’s commitment to ensure Australians were not prevented by lack of income from accessing quality medical and hospital treatment.

Labor’s Distinctively Australian Reform Path

While the Accord strengthened the centralised system of wage fixation, Labor radically deregulated the financial system radically. Long-standing bureaucratic controls over exchange rates and interest rates had been rendered increasingly unworkable by the growing scale and sophistication of global capital markets. Frightened by Liberal fear-mongering during the election campaign, investors and speculators shifted hundreds of millions of dollars offshore, prompting Labor within days of its election to announce a 10% devaluation of the Australian dollar. The decision was supported by the Reserve Bank, The Treasury and – in an early test of the Accord – by the ACTU, which had provided assurances that unions would not use the inflationary impact of a cheaper dollar as the basis for unreasonable wage claims.

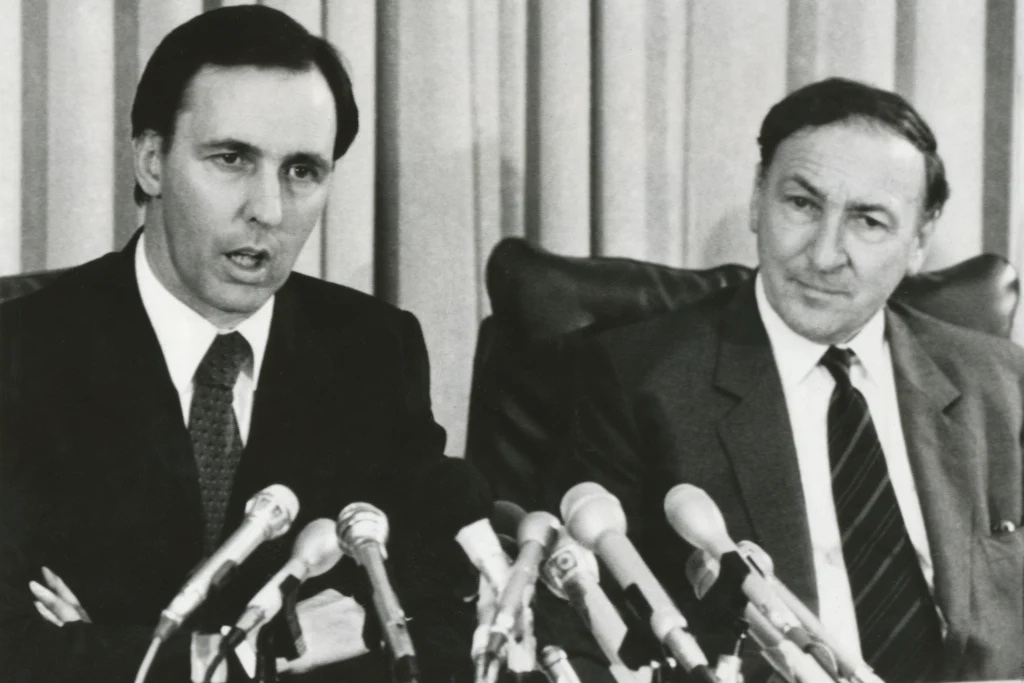

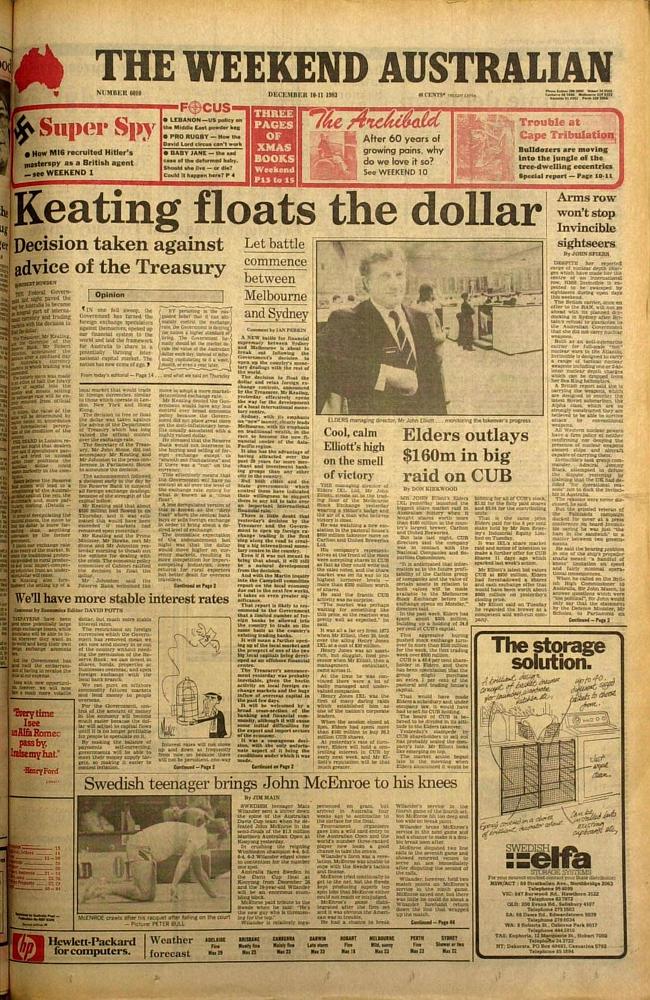

A more fundamental reform came in December 1983, when Treasurer Paul Keating announced the abolition of existing exchange controls and allowed the value of the currency to ‘float’ on international markets. While arguably unavoidable, Labor’s float of the dollar was the single most influential decision of the entire Hawke-Keating period, its reverberations continuing for a decade and more. It showed a new decisiveness in tackling national economic reforms, and a welcome clarity in communicating their necessity. It forced change on inward-looking and protected industries, galvanised a sclerotic financial sector, and opened the door for the transformation of an insular and uncompetitive Australian economy. In the same vein, foreign banks were licensed to operate in Australia, providing needed competition to the well-entrenched domestic institutions.

Elected in the midst of a recession, Labor saw economic growth recover to more than 5% by the end of 1983, with strong jobs growth, falling unemployment and falling inflation. Industry Minister John Button developed industry plans for the steel and car industries. Imbued with the summit’s tripartite approach emphasising collaboration by government, unions and business, the Button plans promoted structural adjustment in manufacturing industry by negotiating agreed programs of reduced tariff protection, increased exports, and workforce retraining and redeployment.

In a decade when conservatives in the United States and United Kingdom under Thatcher and Reagan aggressively embarked on small-government goals – notably, dismantling of welfare systems and the promotion of market-driven interventions – Australian Labor pioneered a distinctive reform path. Through an intimate partnership with the trade union movement and an activist role for the public sector, this distinctively Australian, and distinctively Labor, response to the economic challenges of the day achieved egalitarian outcomes, fiscal discipline and electoral success. In this sense the Hawke and Keating governments differed from, and predated, the centre-left renewal projects – broadly described as ‘third way’ – by Blair in the UK and Clinton in the US.

Keating later declared: ‘We didn’t call what we were doing the Third Way. For Australia we saw it as the only way.’

A Broad Agenda

The new government immediately fulfilled its ‘no dams’ campaign promise, banning construction of a hydro-electric dam on the Gordon river that would have flooded the Franklin river in the iconic wilderness region of south-west Tasmania. On 1 July 1983 the High Court upheld the ban, finding it consistent with Australia’s international treaty obligations under the World Heritage Convention. This represented a landmark expansion of the Commonwealth’s constitutional powers (and was built in part on a dissenting 1936 judgement by High Court judge, later federal Labor leader, H V ‘Doc’ Evatt).

Later, Cabinet’s decision to permit uranium mining at Roxby Downs breached the party platform, which opposed uranium mining on environmental, energy and security grounds. In line with the Hawke Government’s new operating principle of Cabinet solidarity, which differed from that of the Whitlam period in binding ministers to support decisions in the Caucus, the Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs Stewart West resigned from Cabinet. Amid emotional scenes, the 1984 ALP National Conference accommodated Cabinet’s decision with the so-called ‘three mines’ policy, permitting mining at Roxby Downs (SA) and the existing mines of Nabarlek and Ranger (NT).

Labor’s landmark Sex Discrimination Act outlawed discrimination on the grounds of sex, marital status or pregnancy in employment, education and services – including in the private sector; it also outlawed sexual harassment. The legislation was a particular triumph for Senator Susan Ryan, the first woman to serve in a Labor ministry; it too gave force to international treaty obligations, in this case the UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination. As Education Minister, Ryan also secured real increases in funding for schools, including a form of means-tested grants to government schools. When Labor came to office, only one-third of students were completing Year 12, and those mostly from higher-income communities; Labor’s funding soon doubled that – an achievement Hawke repeatedly trumpeted as an enduring reform.

Labor’s economic reform agenda in turn complemented a new assertiveness in Australian foreign and trade policy. On a visit to Washington in June 1983, Hawke underlined Labor’s commitment to the US alliance within an ‘independent and self-respecting foreign policy based on a cool and objective - hard-headed if you like – assessment of Australia’s genuine national interest.’ In this spirit, Hawke provided Parliament with the first official explanation of the function of the secret joint US-Australian facilities – at Pine Gap, Nurrungar and North-West Cape – emphasising their contribution to deterrence, arms control and nuclear non-proliferation. Australia also kept some critical distance from the Reagan administration’s Strategic Defence Initiative (‘Star Wars’) project.

With former Leader Bill Hayden as Foreign Minister, Australia sought closer engagement with the Asia-Pacific region, initiating negotiations that led to the creation of the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone in 1985, and seeking to reengage with Vietnam and Cambodia as part of a post-conflict settlement in Indo-China. Hawke spoke of ‘enmeshment’ with Asia, including a much closer relationship – economic and political - with China, then just commencing its re-emergence into the international community. Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang visited Canberra in 1983 and Hawke repaid the visit in 1984. In the same vein, facing Opposition Leader John Howard’s implicit stoking of anti-Asian sentiment, Labor vigorously defended the nation’s policies of non-discriminatory immigration and multiculturalism.

An early crisis came when the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation informed Hawke that it believed a Canberra-based KGB spy Valeri Ivanov was cultivating Labor’s former national secretary, then lobbyist, David Combe. The Government severed its ties with Combe. Ivanov was promptly expelled – but a leak about the expulsion forced Special Minister of State Mick Young to resign. A testing Royal Commission under Justice Robert Hope vindicated the Government’s handling of the affair. Shattered, Coombe was later posted as trade commissioner in Canada.

The introduction of Medicare, increased schools funding, and other social wage initiatives, were all the more impressive given Labor’s simultaneous focus on fiscal discipline. Elected with a program of social expenditures designed to provide a Keynesian boost to economic growth, Labor found it necessary - thanks to the high projected deficit bequeathed by the Fraser Government – to discipline its spending, while also promoting social equity. In the same vein, decisions to impose an assets test on the age pension and a tax on lump sum superannuation were designed by Cabinet’s empowered Expenditure Review Committee to ensure income transfers were focussed on the needy not the well-off – that is, to achieve both fiscal and equity goals.

Labor amended the Electoral Act to introduce public funding for political parties complemented by disclosure of donations, overseen by a new Australian Electoral Commission. The legislation also increased the size of the Parliament for the first time since 1949: the House of Representatives increased from 125 to 148 members and, as a consequence, the Senate from 60 to 76 senators.

Riding high in the polls, Hawke called an election for 1 December 1984, a year earlier than necessary; his timing was also designed to resynchronise the election calendar after the double dissolution of 1983. The campaign featured Australia’s first televised leader’s debate, between Hawke and Opposition leader Andrew Peacock. After a draining eight-week campaign, Labor was returned with a comfortable, though reduced, 47.5% primary vote. In the enlarged House, Labor held 82 seats, a majority of sixteen.